While I’m someone who is open to all theoretical frameworks and methodological styles (quantitative, qualitative, spatial), much of my research uses neoinstitutionalism and institutional theories. I’m considered a neoinstitutionalist, by all measures. I study rules and norms. I strongly believe that analyzing rule formation, maturation and erosion can help us understand how resources can be better (and more cooperatively) governed. This conceptual framework, much of which is derived from the late Elinor Ostrom’s work on commons governance, worked pretty well when I lived in Canada (for almost half of my life).

Moving to Mexico gave me a very serious cultural shock, both as an individual and as a scholar. While I’ve studied Mexican environmental policy for most of my academic life, much of this work I did while studying (as a PhD student) and working (as a faculty member) at a Canadian university. My perception of Canada has always been that it is a country with strong rule of law and Canadians as individuals with a very strong sense of compliance with laws and rules. My perception of Mexico has been (for most of my life) that it’s a country with very weak rule of law, with Mexicans (generally speaking) as individuals who routinely give themselves permission to violate rules and laws. This is, of course, a VERY broad generalization. Of course there’s millions of Mexicans who comply with the law and with generalized rules and norms of behavior. But I don’t think my perception is all that far off. Anecdotes and jokes about Mexicans abroad say that they will litter on the street in Mexico, but will pick up their trash in Canada and elsewhere. I myself have been witness to this behavior, many, many times. After all, I lived in Canada for decades. The Canadian Superior Court Judges Association, in fact, makes this point on Canadians and rule of law quite strongly, and I quote:

Our laws embody the basic moral values of our society. They impose limits on the conduct of individuals in order to promote the greater good and to make our communities safe places to live. It is against the law to steal, to injure another person, to drive recklessly or to pollute the environment, to name just a few of the countless ways the law is designed to protect us. We are said to be ruled by law, not by those who enforce the law or wield government power. No one in Canada is above the law. Everyone, no matter how wealthy or how powerful they are, must obey the law or face the consequences.

I don’t really follow the literature on rule of law as much because I don’t study corruption or quality of democracy (although I have colleagues at CIDE who do study corruption and impunity in the public sector, like my colleagues Dr. David Arellano Gault and Dr. Mauricio Merino Huerta). Yet, non-compliance with rules, particularly non-compliance with environmental regulation IS part of what I study. My earlier research looked at compliance with environmental regulations in the leather and footwear industries. I have been a fan of voluntary (suasive) environmental policy instruments, whereas Mexico uses primarily command-and-control, regulatory instruments. So, while the analysis of rule of law is not my direct field, it does touche upon what I investigate, and thus I have had to delve into this body of literature.

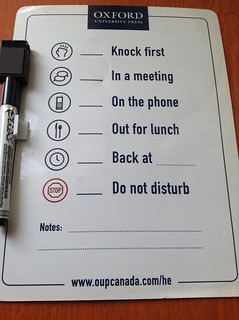

Photo credit: Cliff on Flickr

The biggest problem my research on Mexican environmental law and policy has found is the Mexican industries’ lack of compliance with standards and regulations set forth by SEMARNAT, the Mexican environmental ministry, and by the state and local authorities. PROFEPA, the Mexican federal attorney for environmental protection, has historically faced a chronic lack of institutional and organizational capacity (too few inspectors to ensure that regulations are enforced). In this scenario, it is frustrating to try and understand how resource-governing rules emerge, become institutionalized and ultimately, become eroded or face institutional instability.

This frustration has led me to reflect on whether it is a smart idea to study rules in an unruly country. I’m not the only one concerned with rule of law in Mexico. A quick search on Twitter yielded plenty of results, concerns and commentary on rule of law (or lack thereof) in Mexico. Multiple analysts consider rule of law as one of the biggest challenges facing Mexico. Even Arturo Sarukhan (former Ambassador of Mexico to the United States) has written on how rule of law in Mexico is weak and impunity is rampant.

Thus, I believe it’s understandable why I find it so frustrating to study rules in an unruly country. While I certainly don’t believe Mexico is on the brink of collapse, it was even more frustrating to find out that The World Justice Project‘s index for impunity by high-ranking government officials positions Mexico as one of the countries where corrupt officials would get away with their actions. I quote:

In Mexico, for example, where 80 percent of people said the officer would go free, only 1 in 1,800 persons reported for corruption in 2010 was held accountable.

I suppose that as a neoinstitutionalist I could continue to observe how formal and informal rules of water and solid waste governance emerge in a system with low rule of law, but the more I think about this, the more I believe my work in environmental regulation would need to focus on strengthening the rule of law in Mexico. To do this we need better enforcement and actual sanctions. This will be an interesting challenge for my future research agenda.

Recent Comments