I almost died this summer of 2022. Four times.

This summer, I learned (the hard way) 4 lessons about health, overwork, and life as an academic.

(1) “If you don’t make time for your wellness, you’ll be forced to make time for your sickness” — Joyce Sunada

I was, in fact, forced to take time off because of COVID and its sequelae. This week I sat down with my physician and we did a “post mortem” of my illness. He said: “you have overworked for a very long time. You push your physical limits all the time. You are very energetic, active and passionate about your work, but you keep pushing yourself. Not healthy”.

This was really embarrassing to hear from my treating doctor and a wake up call: I keep advocating for NOT overworking, and yet, in some twisted way, I kept doing it because it didn’t feel (yet) like I was exhausted.

Until it did.

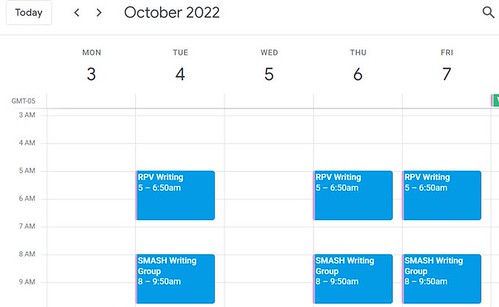

In May, I went to Germany and the US. In normal times, and under normal circumstances, these two trips would have been a piece of cake because I am/was used to travel All The Time. However, this year has been particularly busy with teaching, administrative duties, and course preparation, reading theses, providing feedback. SUPER BUSY.

So (we all know where this is going…) I did not pay attention to my tiredness (in May 2022) because I attributed it to jet lag from going to Germany. But when I went to Washington DC, I was already tired, and kept pushing myself. The last day, two dear friends of mine said: “you look TIRED. You need to take care of yourself. We need you healthy.” (Thanks, Leila and Sameer).

When I returned from Washington DC, my Mom got COVID, so I had to take care of her. She had a very mild case, but I think being stressed about her health was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I then got COVID, and my body was already very weakened from travel, stress and overwork.

We all know how this went. I spent all of June sick (and taking care of a COVID patient and then getting it myself!), July so sick with COVID sequelae that I almost died 3-4 times (depends on how you count), and August in slow-but-steady recovery.

The second lesson is, therefore:

(2) Pay attention to signs of potential burnout.

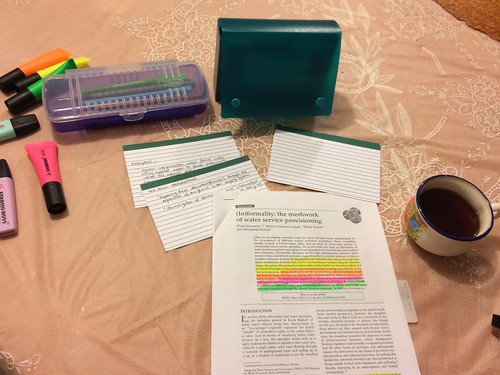

I had felt burnt out before and could recognise the signs: de-motivated, didn’t want to read academic articles, exhausted with no apparent reason. But again, the travel hid all the signs. I had them all, I just didn’t see them. This is particularly important in academia: we attribute burnout to other factors: “maybe I’m just tired this week”, or “it will get better once I get all these 457 things out of the way and I can clear my deck”. Well, I got news for you: the deck is never cleared.

I’ve written on my blog several times about the importance of not overwork, but for some reason, when it came down to it, I did not recognise the signs that clearly showed anybody except me (because I was too blind to see them) that I was entirely, completely and absolutely burnt out.

(3) Seek support (and this includes emotional support).

In desperation about my lack of health improvement, I tweeted “I’ve lost all interest in academia and all I care about is being healthy again”. I received HUNDREDS of responses sending love and wishes for good health.

The bird app can be hell sometimes, but it is definitely a truth that my Twitter community kept me afloat (my Facebook friends also deserve a very big Thank You because they kept checking in on me, daily). I did not realize I could have so much support from the Twitter hellsite, and it really helped me improve. I received so much emotional support that I began feeling extremely hopeful that I would be, eventuallly, able to recover fully (and I am currently in the process of doing just that).

My physician has prohibited me from returning to my usual hyper-energetic self. He said, deadpan: “I want you to return to normal people’s normal, not YOUR normal — this means dialing it down on the workload and intensity”. As a neoinstitutional theorist, I follow rules to a T. And I have no plans of dying any time soon, so I am paying close attention to my body and how I well am feeling on an hourly, daily and weekly basis. If I need to take a rest, I take it, work life be damned.

But I did not get well UNTIL I went to see a pulmonologist.

So the fourth lesson is:

(4) Be your own advocate for your health.

I went to a general MD, then the otorrhinolaryngologist, and it wasn’t until I went to the pulmonologist that we figured out what was wrong and how to fix it. COVID is an extraordinarily strange illness, and it’s so unpredictable nobody really knows the potential outcomes. I am lucky to be alive. Given that I had an immune system weakened from overwork and exhaustion, it was pure sheer luck that I made it alive and in one piece.

What really brought home the severity of my illness and the importance of taking care of myself was this utterance by my pulmonologist: “you survived this time – you probably won’t get another chance – your body won’t withstand another crisis like this. TAKE CARE!”.

YIKES.

In closing: Academic friends: look at yourselves in my mirror. Take care of yourselves *before* you are forced to take time off to take do exactly that: take care of yourselves.

I HAVE, finally, learned my lesson.

Recent Comments