This semester has been a bit more hectic than I expected, and keeping everything under control hasn’t been an easy task. But despite whatever challenges I face, I am determined to stay on top of the literature. I’ve written before about having a repertoire of reading strategies (quick skim to determine what a paper is about and whether it’s an important one or not, mid-range for when we’re doing literature reviews, annotated bibliographies or in-depth for when we’re preparing for comprehensives or writing a paper).

I do carve time to read every single day, because otherwise I’m not able to be on top of the literature (which I need to be). Last night, I live-tweeted my reading of a paper and that process made me consider writing a blog post on my strategy for when I’m pressed for time, which you can see in my tweets (click on the hyperlink on the time stamp of my first tweet to reveal the entire thread, or on this link).

I received this paper via Twitter from the WIEGO (Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing) Twitter account. This group frequently publishes research in a field I work in: informal waste pickers. I know Sally Roever in person, I’ve read and love her work and we’ve met as well (we met and went for a coffee and a walk this year at ISA 2017 in Baltimore and we had a wonderful time).

When I know an author in person, and I know their work is relevant to my own research, I usually try to read whatever research they just published as soon as possible. So that’s what I did last night. In total, I spent 30 minutes because I paired my AIC Content Extraction Method with my Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump. I knew I was pressed for time (I go to bed at around 9:30pm every day so I can wake up at 4:00am and write), so I figured I couldn’t spend more than 1 hour in this paper. This is the process I followed:

My rule is to never leave anything “unprocessed” (see my protocol for the process that I use to go from downloading an article or a book chapter’s PDF to writing a full memorandum here).

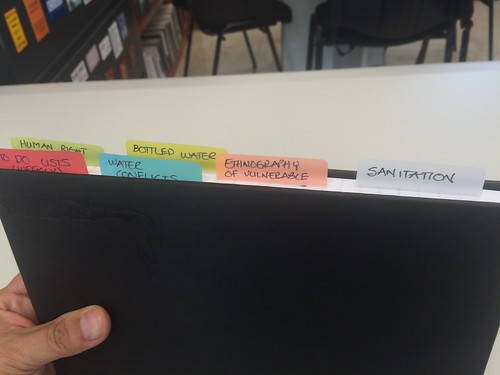

My goal for this paper, despite the fact that it’s really important to my work, was to simply read the Abstract, Introduction and Conclusion (AIC), highlight and scribble and find the main ideas, write an entry (a row) in my Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump for informal waste picking, and file in my “To Process” tray. This way, once I get everything that I need to finish this week out of the way, I’ll get back to reading this article in detail.

To do an AIC, I usually read the Abstract first, then the Introduction, then the Conclusion. Because I knew that I didn’t have the time to write a full memorandum, to read the paper in detail, and even to write a synthetic note, I decided to write an entry in my informal waste pickers’ Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump. This is the very least I can do, and this allows me to know which articles are important to read and get back to.

Even though I was reading, I also took the time to post my process on Twitter, and answer questions as I went along.

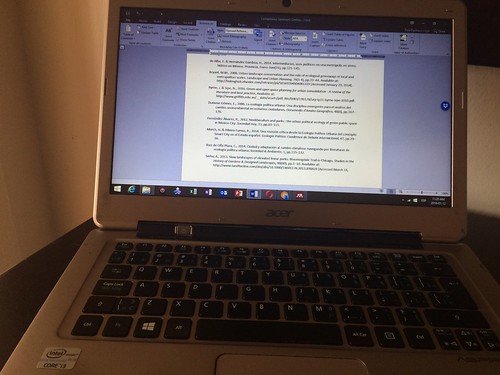

As I read the paper, I uploaded it on to Mendeley, cleaned up the reference, and typed the content of my scribbles on to a Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump row, as you can see below.

It’s important to note that all I did was read Abstract, Introduction, Conclusion, scribble notes on the margin that help me understand and process the information in this paper, and highlight relevant passages in those three sections of the paper (which give me a good overview of the entire journal article), and then type these notes into a row in my Conceptual Synthesis Excel Dump. Because I know I’m going to have to come back to this paper, I don’t simply file it, but I locate it in my “Processing” tray (see my Four Trays Method for Filing and Organizing).

Once I’m done with a paper, I usually file it using a magazine holder (as I’ve outlined in this blog post).

For me, using this method ensures that

- (a) I stay on top of whatever newest research is being published

- (b) I carve time every day to read

- (c) I have notes for the paper and

- (d) I will come back to read this paper in more depth.

Overall, this entire process took me 30 minutes. I could notice the gaps in learning once I finished the AIC process: I could tell that I hadn’t read about the 4 cities, neither the introduction nor the conclusion had details about the case studies and specific insights but were more general. So I know for a fact I need to come back to this paper, but I’ll do that when I know I have more time, or when I have to write something on informal waste pickers. But at least I already have read some basic information off the paper, and I have an Excel dump entry to check and review.

Obviously, there are papers that are harder to read, therefore taking much more time. Walsh 2015 on mineral springs and primitive accumulation in Mexico, and Kaplan 2011 on drinking water fountains and water coolers both took me an entire week at about 20 minutes a day to finish reading them. These articles were DENSE and full with information. I had to take a few days to process them. But I read a little bit of each one every single day.

Hopefully this process will help my readers keep up with the literature! I know how hard it is with heavy teaching loads to stay on top of the literature (I am well aware that my previous 2-1-2 was not the worst – there are scholars who have 4-4 or even 5-5).

One of the reasons why the bottled water market remains as is (in a position of domination whereby it’s one of the top 5 most profitable businesses out there, together with scholarly publishing, and yes I recognize the irony in all of this), is the fact that there are institutional and structural factors that drive increases in bottled water consumption. One that I find particularly galling is the fact that there aren’t enough drinking water fountains within cities’ territory. Water provision is a public service that is usually the responsibility of cities. It’s one of the many public services that local governments are entrusted with, alongside garbage collection, treatment and disposal, parks and public gardens, and street road lighting. One of the many ways in which cities can reduce bottled water consumption is through the provision of public water fountains.

One of the reasons why the bottled water market remains as is (in a position of domination whereby it’s one of the top 5 most profitable businesses out there, together with scholarly publishing, and yes I recognize the irony in all of this), is the fact that there are institutional and structural factors that drive increases in bottled water consumption. One that I find particularly galling is the fact that there aren’t enough drinking water fountains within cities’ territory. Water provision is a public service that is usually the responsibility of cities. It’s one of the many public services that local governments are entrusted with, alongside garbage collection, treatment and disposal, parks and public gardens, and street road lighting. One of the many ways in which cities can reduce bottled water consumption is through the provision of public water fountains.

Recent Comments