There’s a lot of writing around about “writing retreats” and I had wanted to write about this for a long while, but I had not been able to do so until today when Dr. Katie Rose Guest Pryal asked me what I thought about writing retreats (you should read her entire thread, which starts here:

What I’m advocating for, here, is the writing retreat.

Broadly construed.

— Dr. Katie Rose Guest Pryal ♿️🎾📘 (@krgpryal) January 21, 2020

I responded with a thread of my own, but I wanted to start by saying that I travel a lot, and I try as much as I can to write every day throughout the duration of my trips. One of the main requisites that I demand from hotels is desk surface availability. That means that the room where I stay, should have at least a desk, preferably with a lot of working surface.

When I have some time (i.e. when I arrive early to a conference or workshop or field trip), I try to make the most of my travel by writing at the hotel, and taking that extended period of time as a “mini-writing retreat”. One of my favourite was the one I took in Vancouver Island in 2012.

Last year, I took up a visiting professorship at IHEAL in Paris (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris 3) where I taught 2 very short courses (Comparative Public Policy and International Development in Latin America). I taught in Spanish, which is something very rare for me. I do most of my teaching in English, and I expected them to ask me to teach in French, or English, so when I was asked to teach in Spanish, it threw me for a bit of a loop and I ended up having to prepare class more than I expected to.

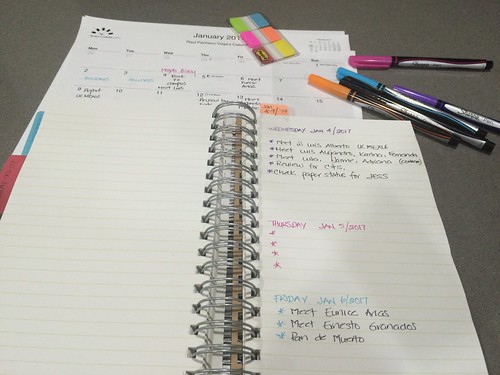

As most of everyone who follows me know, I’m super close to my parents, and more specifically, to my Mom. She is in excellent health (thank God!) and while she is not in any way, shape or form disabled, she’s an older person and therefore she has to be careful with her health. While living in Paris, I taught 2 days and could write the other 3 (I did take weekends off, something that I very strongly encourage people to take, if their circumstances allow). Having full days to think, research, write, etc. was glorious. Since my Mom is a professor I was able to bounce ideas off her all the time. She worked on her own stuff and I worked on mine, but we also chatted. I was able to rent a two-bedroom house in the banlieue of Paris, incrediby close to Paris (door-to-door from my house to IHEAL I did literally 35 minutes).

Anyways… visiting my Mom on weekends (we live in different cities here in Mexico) and having a visiting professorship that gave me full days for research and fieldwork were (and one of them continues to be) two of the ways in which I carved time to write. I spend time with her. BUT I also have several very long periods of time when I can just focus on my writing. But back to her health (and mine). This year, my Mom injured one of her thumbs (the right hand one) and her two shoulders. This meant that, while she’s entirely independent, she needs help. She needs help in extraordinarily small things: reaching up to get stuff from the top shelves, tying her shoe laces, etc. Very tiny things that do not affect her independence, but that need to be done. Obviously, washing dishes and cooking become really hard to do for her. So, while I not taking care of her all day long (because she doesn’t need to, she’s healthy and in good shape), I did need to help her sometimes with small minutiae. I mention this because the long, extended periods of writing can/do get interrupted by doing these small errands.

By the way, she’s MUCH better now, thanks for asking.

Thus, responding to all 3 prompts that Dr. Guest Pryal shared, I do agree that writing retreats work. I had my mini-writing retreats in Paris (and yes, trust me, the “sitting in a cafe right by the Seine having coffee and writing” visual is a lot more theory and a lot less practice (Paris is ultra expensive and if you want to sit in a cafe and spend hours writing, expect to be paying LOTSA EUROS, which I would assume a writer wouldn’t do). In practice, I wrote a lot at home, which was glorious. It was amazing because after a long writing session, we would simply take the bus and the RER and head out to Tour Eiffel and walk around, sit down and have a coffee by the Seiine, etc. Or we would go to the Versailles Museum. Or shopping in Champs Elyseés.

Here is the BUT…

I can and could do this because my care work is on minutiae. My Mom is perfectly capable of driving and she drives herself anywhere. But I do like being of service to her, so I often drive her around on weekends. This, obviously, makes the dynamic of long-blocks-of-time difficult And I do really simple care work! I can’t even begin to imagine the challenges that parents, or folks who need to take care of themselves AND of others (the number of people I know dealing with their own disabilities AND with care work I know is staggering and I admire them much).

… are unique. This is why I am sometimes uncomfortable calling my blog and tweets “advice on how to academia”. I can’t give advice. My circumstances are very unique and in some ways, very privileged (let’s not forget that I have been dealing with chronic pain and fatigue too)

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 21, 2020

At the peak of my eczema/dermatitis/psoriasis/chronic fatigue/chronic pain, I was unable to THINK let alone write. I am six months behind on everything because I spent six months struggling with bad diagnoses, incompetent physicians and having to teach and fulfill my commitments. I share my life in such an open way because I believe that sharing my story may in some ways help students, faculty, practitioners, society at large. I do have some privilege, but I also face many challenges. I am just starting to get back into the groove after 6 months of pain.

In closing: do I believe in writing retreats? Sure. But I am not sure how we can organize one that could be sensitive to the needs of parents, people with care work, disabled/marginalized individuals, etc. Academia is very ableist, as I have repeatedly said.

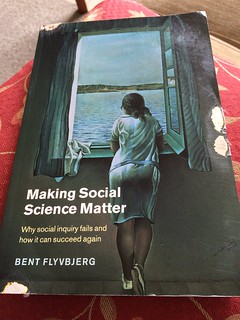

This is perhaps why I love Joli Jensen’s mantra of “writing regularly by having constant, low pressure, low stakes contact with a writing project that we enjoy”

How you make that work is something only YOU can decide. Nobody can decide that for you.

</end thread>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) January 21, 2020

I am grateful to Katie for asking me to share my thoughts on writing retreats, because I do believe in them, but since academic populations are so heterogeneous, we can’t generalize on their usefulness.

Recent Comments