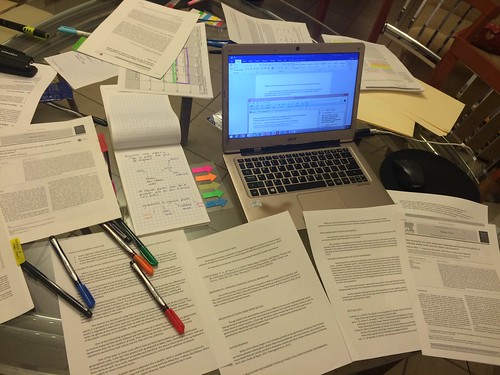

As I write this series of blog posts on writing the thesis/dissertation, I get serious flashbacks of the period when I had to write my doctoral dissertation. The funny thing is, I have also had flashbacks from when I wrote my Masters’ and my undergraduate theses. Despite the fact that one was in chemical engineering, one was in economics of technical change and the doctoral dissertation was multidisciplinary (though primarily comparative politics, public policy and human geography), I think I’ve approached writing my theses in the very same way: get all data first, then analyze, then write.

I am writing this post from the viewpoint of someone who has supervised theses and dissertations, though in the future I think I will write one for advisors. I’ll start from the baseline that you (undergraduate, Masters student/doctoral candidate) have already done everything except the thesis. This implies that you’ve conducted fieldwork, done laboratory experiments, conducted archival work, etc.

In my thread, I also discussed the process I underwent (writing comprehensive exams AND also developing and defending a dissertation proposal). I explain this because the process that helped me develop my dissertation’s theoretical underpinnings and find the gap in the literature I was filling was not the reading and synthesizing I did for my comprehensives (comps) but rather the one I did for my dissertation proposal.

First, I want to list resources written by a few other scholars who discuss this very topic.

2) Dr. Patricia (Pat) Thomson @ThomsonPat https://t.co/SJYG2UZnwb who has written books on how to supervise PhD students, and a wealth of other volumes on these topics.

3) Dr. @evalantsoght who published The A to Z of the PhD trajectory https://t.co/BUk2rvHAEe fantastic book

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

4) Dr. Petra Boynton (@DrPetra) who wrote The Research Companion as a guide for researchers https://t.co/uyVo28L1bB

5) Dr. Patrick @PJDunleavy Dunleavy who wrote “Authoring a PhD” https://t.co/0UIyI3Q7n0 a book I refer to on a regular basis when talking with my own PhD students.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

Obviously, I recommend that you also read everything I’ve written on topics related to the PhD thesis writing, including my previous post in this series on thesis writing, timing and structure. I also recommend looking at my own set of Reading Notes of books I’ve read on how to do a PhD. On Twitter, I explained why I buy and read books on the PhD process given that I already have my own PhD. Obviously I don’t need any of these books, but I purchased over a dozen volumes with my own money so that I could read them, draw insights from them, and improve my supervisory style therefore becoming a better thesis advisor.

You can access all my reading notes here https://t.co/jPcfvf8Plz

Having provided all these resources, I should warn you that I’m writing from my Mom’s house in Leon, and therefore I am in no way, shape or form close by any of my books on “how to do a PhD thesis”.

So…

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

DETERMINING THE SCOPE OF THE THESIS/DISSERTATION

Establishing how much work is necessary to obtain a specific degree (undergraduate, Masters, PhD) is necessarily something students and doctoral candidates should discuss and agree upon with the supervisory committee. I have written before on how I define a doctoral degree and what a PhD entails. I’ve also written on the differences between an undergraduate (honors) thesis, a Masters’ and a PhD dissertation (see link in the tweet below). By the time you want to start the thesis or dissertation, you should have agreed with your committee on the scope, breadth and depth of the thesis and dissertation. I assume in this blog post that you’ve already had this conversation (if you have not, this would be a good time to have it!)

I am going to do this thread based on my recollection of books I’ve read.

I’m also assuming you’ve discussed with your PhD committee and/or your thesis advisor(s) the scope of your work https://t.co/eajzAEDJ62

There’s an intermediate step between PhD comprehensives and thesis.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

READING ENOUGH TO FIND THE GAP IN THE LITERATURE, THE CONTRIBUTIONS (THEORETICAL AND/OR EMPIRICAL), AND STARTING THE ACTUAL WRITING PROCESS

In my Twitter thread, I explained that there was an intermediate step between doing comprehensive exams and writing the thesis. I think it’s important to mention that processes vary by degree (undergraduate, Masters and PhD) and by country/region/discipline, etc. I am mostly familiar with social science and humanities theses, but I also understand how STEM theses are written.

Because I did my PhD in Canada and I’ve supervised students there and in Mexico, I am most familiar with the processes that universities in these countries follow. I WAS going to do my PhD in England, though, and I’m aware that many programs in the UK and Australia do not have qualifying/comprehensive exams nor coursework and thus go direct to thesis.

The way I did my PhD was slightly complicated. I did comprehensive exams (written questions and oral defense) and THEN I defended a dissertation proposal. The work I did for the latter (review of the literature, mostly, and preliminary fieldwork) basically set the stage for my PhD dissertation. The reading (and systematizing) I did for my comprehensive exams helped me with my dissertation insofar I demonstrated I knew the literature in my fields, but they were much broader. After I passed, I still had to go and delve into different sets of literature because I cross disciplinary boundaries to prepare my dissertation proposal.

WHEN IS THE RIGHT TIME TO GET STARTED WRITING THE THESIS/DISSERTATION?

I started writing my PhD dissertation in earnest when I returned from my fieldwork. My PhD students started writing as soon as they returned from the field. This was because most of them have done their dissertation as a set of 3 papers. The only one of my PhD students who did a book manuscript ALSO started writing AFTER he had done fieldwork.

Because my doctoral students writing 3 papers did fieldwork in 3 different places, what I recommended to them was to start writing the results sections of all three papers (and the methods and data sections). THEN I asked them to write each paper separately.

To summarize: I believe the best moment to start writing the thesis/dissertation is when you are entirely sure you’ve collected enough data/archival material and thus you can write then the full manuscript in earnest.

DEVELOPING A TIMELINE FOR THE DISSERTATION/THESIS PROGRESS

Now, if you’re going to write an entire thesis, you need to have a plan. I have written before about the importance of planning your thesis/semester/year (you can read all my posts on organization and time management here and on planning here). While I started writing the Twitter thread assuming that the student had already done the work of planning their progress, as I wrote the thread, I realized that it was important to outline the steps necessary to plan, particularly under conditions of uncertainty (like our current COVID-19 pandemic)

… COMFORTABLY planned for. This is fundamental, even more so in the context of pandemics and social unrest.

There will be things that will distract you, de-stabilize you emotionally and require you to process them. Make space (mental) and time for processing these emotions.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

Several institutions have automatically added one year of funding for graduate students given the pandemic, but this concession isn’t universal. So I think that we ought to be realistic and consider the worst case scenario (potential derailing, no additional funding) and plan for this. I’m always a worrier.

I always tell my students to plan for “When Shit Hits The Fan”. Because shit will ALWAYS hit the fan (trust me on this one: I broke up with my former partner as I was about to defend). For me, the best planning technique is the Gantt Chart. I also recommend that all your Overview Devices (Dissertation Two Pager, Dissertation Analytical Table, Global Dissertation Narrative, and Thesis Project Gantt Chart are all consistent with each other).

And then the pandemic happened.

To be perfectly honest, I have not felt emotionally stable until about now-ish, which is the end of May 2020 or beginning of June 2020.

I would expect my PhD students might feel emotionally de-stabilized, and thus, we build some room for it. pic.twitter.com/pFOzKZ1FRm

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

Note that in my edits to their Gantt Chart, I inserted “pivoting to new research strategy and data collection”. Doing fieldwork during a pandemic of this sort is risky and I would consider it dangerous https://t.co/yUPnyfiMFX

Doing this pivoting requires time to think, etc.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 30, 2020

The one thing that I don’t think we say frequently enough in our conversations with students is that EVERYTHING EVOLVES. I have changed my priors around many things. Fieldwork, new reading, delving into other literatures changes the way I think. My writing evolves, my thinking does too. An example:

I’ve done fieldwork in Paris many times over the years, but it wasn’t until last year that I lived there for a semester that I realized a lot of things that reading the literature didn’t reveal. Conducting interviews in French, reading French scholarship really changed how I think.

I say this because, if you are thinking that you’ve collected all the literature, data, etc. and now you’re just going to sit down and write the thesis and it’s going to feel like a linear process, you’re deluding yourself.

THAT’S NOT HOW ANY OF THIS WORKS.

As you write, you’re going to realize new insights, develop new ideas. Refine your argument. Redraft text. Revise it. And then you’re going to find out that the final abstract, introduction and conclusion of your dissertation aren’t going to be exactly the ones you first thought they would.

Now, on to the other key question that another PhD student asked me:

HOW DO I ACTUALLY START WRITING MY THESIS?

The previous paragraphs showed the pre-requisite conditions to start writing. Now, on to the actual process of “starting to write the thesis/dissertation”. Here’s how I think of the process, how I wrote my theses, and how I tell my students to write their theses.

1) Write a suggested table of contents.

In my Twitter thread I said that I did not remember if I had written a blog post on how to develop suggested tables of contents for theses or books. As a matter of fact, I did! Here is the first post of this series, which focuses on structure, content and timing of the thesis..

Suggested table of contents for a thesis/dissertation off the top of my head, and based on my Dissertation Analytical Table (DAT) and on my Dissertation Two Pager (DTP) devices

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Paper 1.

4. Paper 2.

5. Paper 3.

6. Concluding chapter

… basis”?

Fear not. What I tell my own students is to

(a) break down their chapters and papers into smaller pieces https://t.co/DhllyI1Ptp

(b) write memorandums that develop each one of these small pieces https://t.co/q3gEpJxH4b

(c) make it a daily goal to work on ONE item

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 31, 2020

Maximum 2-3 items.

Studying for a degree is overwhelming enough, so you don’t need to add more stress to your life (we’re in the midst of a global pandemic, living at home, there is social unrest and worry, there’s more than enough worry in our lives). I always recommend that my students develop a structured working routine. Obviously, current conditions require a lot of flexibility and transitioning and that’s where the conversation with professors and supervisors is important (and the empathy and kindness of those advisors is FUNDAMENTAL).

This was my structured routine before the pandemic https://t.co/zszfikTn6V

I find that for me, structure and routine help.

BEING THIS ORGANIZED AND STRUCTURE MAY NOT WORK FOR EVERYONE.

It works for me, you do you, as you were.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 31, 2020

TO RECAP: How to start writing a thesis (I assume you have been in conversations with your supervisory committee):

1) Write a draft of your thesis outline/table of contents.

2) Apply backcasting techniques from the date you need to submit the thesis and plan backwards.

3) Build a Gantt Chart with enough buffers to account for everything that is going on right now (potential factors that may derail your progress)

4) From your Gantt Chart, break down the tasks that you need to do and realistically can do, and schedule those throughout weeks/days.

… until you develop each one of the chapters.

I’m going to see if I can do the “thesis” version of the diagram that shows how I backcast an R&R https://t.co/HrGNtMINhk

Ok, NOW I AM done with the thread.

</end thread>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 31, 2020

5) Account for the time that it’s going to take you to assemble the full dissertation and make it entirely coherent (aka making sure that The Red Thread/Throughline is there). https://t.co/ByLSHh3dU6

Good luck!

</end thread>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) May 31, 2020

WHAT ABOUT UNDERGRADUATE AND MASTERS STUDENTS?

I am sure many of you who read this blog post will be asking yourselves, but what about us, who are not doing a PhD dissertation, and instead are doing an undergraduate or Masters’ thesis?. The answer is simple: this process works for EVERY SINGLE LEVEL OF STUDY (undergraduate, Masters, PhD). What you need to adjust, obviously, is the SCOPE, DEPTH AND BREADTH of the thesis. This adjustment comes from a series of conversations between the supervisory committee and the student. How much fieldwork, how many experiments, how many journal articles are expected from the thesis, or what kind of analyses are expected from the undergraduate honors thesis, are all questions that need to be answered through dialogues between the supervisor, all committee members and the student.

The process is the same across all degrees: collect all data, backcast from your desired date for defense/submission, develop a daily work routine, work on bits and pieces of the thesis, assemble towards the end, review and revise and ensure consistency across all thesis chapters.

I hope this post is useful to you all (supervisors and students). Though it’s written to help a student/doctoral candidate, I hope supervisors might find it useful to provide guidance.

Read my other blog posts on this topic:

Really very useful and insightful writing