Funny how some ideas have grounding on different disciplines and yet, we all end up learning more or less the same concept across several of them. I first heard of the concept of future studies (aka futurology) and its idea of backcasting during my Masters’ programme. In particular, the strategic planning literature uses the idea of backcasting first posited in future studies and then adapted to strategic management to introduce how we think about pathways and trajectories towards reaching a goal. I remember I used to love the journal Long Range Planning and would spend entire afternoons reading full volumes of journal issues at the Koerner Library at UBC, and at the Manchester Business School library. I also took project management courses during my Masters, and I’m an engineer, so I think about projects in a project-management kind of framework.

In sustainability studies, the concept of backcasting refers to the idea of imagining a sustainable future, and then devising the strategies, pathways and trajectories that would take our society to that point. That’s backwards planning, reverse planning, reverse engineering, etc. You decide on an end point and then you trace the necessary steps back. Reverse-planning a paper and/or a research project works EXACTLY the same way. While I normally would use the word backcasting for designing trajectories towards sustainability, I also often use it to refer to the deconstruction of the process of creating a project and positing all the different pathways and trajectories this can take (this is where mind-mapping techniques also work wonderfully).

Essentially, I reverse-plan a paper or a research project (specifically the outputs) by taking the end date of the project submission (for example, a conference paper submission deadline) and backtracking the steps to achieve what I need to do. I will use an example of a paper I am coauthoring with Dr. Amanda Murdie (University of Georgia) for the International Studies Association conference in February of 2017. Both Amanda and I are really big on organization, so it is REALLY easy to coauthor with someone with the same kind of planning skills.

The paper needs to be submitted at least one week before the deadline (February 23 is our panel), so Amanda and I plan to write the entire paper in the next few weeks. Therefore we are planning to meet a few times in between, and to do some work on our own to contribute to the paper. We have scheduled a couple of meetings in January and at least one in February to discuss the paper submission and the Power Point presentation. The paper draft needs to be perfect by February 16th, which means we need to have a solid draft by February 9th so we can do final editing, formatting, etc. and start thinking about the Power Point presentation right about then.

Now, if you see my calendar for the first semester of the year, you’ll see that I am at a conference February 9 and 10, and that I will be at Indiana University in Bloomington on February 7th and 8th for a short research visit. This means that I basically won’t be able to do any work that week. Therefore, the entire paper draft needs to be ready by February 5th at the latest. That gives Amanda and myself a full month to write the entire thing, do the analysis and so on.

I do this backcasting process for every project I have in the works, again, based on the conference papers I have committed to writing and when the submission deadlines are. If you read my yearly planning process post, you can see that I have at least other four conference papers to write, for sure (2 MPSA, 1 for the institutional analysis workshop, 1 for WPSA, and then I might present again two of the previous ones, with improvements, or write others, I haven’t yet figured that one out).

It is important for me to include here both my work and my coauthors’ work, so I share my calendars, projects, goals and objectives with them so we all know when things are supposed to happen by when and so that we are all on the same page. This is quite important if you’re doing a lot of collaborative work (which I have been doing in 2015, 2016 and now 2017). My coauthors are simply amazing, and they also love doing a lot of this kind of rigorous planning, so it IS easy for me to do the kind of research I conduct with them.

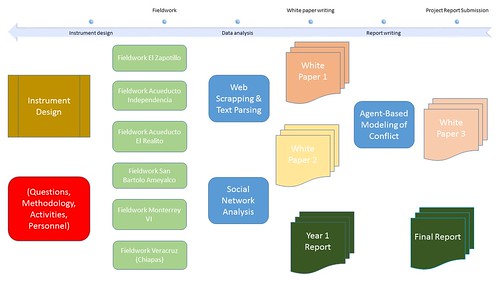

Another example of backcasting for a research project can be found below, for my recently funded grant for water conflicts in Mexico. There are four components (one ethnographic, one of social network analysis, one with agent-based modeling, and one with text-as-data techniques). I am the principal investigator, but there are other three researchers working with me, and two postdoctoral researchers, plus two research assistants and one Masters student and one PhD student. It’s a two-year project, so I backcasted from when we had to write the final report and worked out backwards when we had to do every component. Obviously, the fieldwork needs to happen this year. So that’s how I designed the project to work.

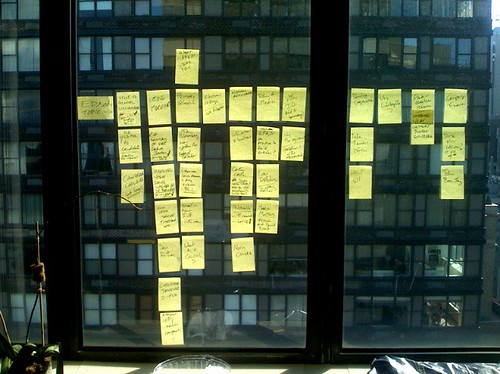

While I do a lot of work on paper, I often simply run to the software tools I normally use. I’ve used Microsoft Visio to design my project plans, I recently explored MindManager to create mind maps and do project plans, and I’ve also used simple Microsoft Power Point to draw the actual project timeline. What I have learned is that when you do collaborative work, and even if you do work solely on your own, storyboarding your project (as Dr. Patrick Dunleavy from London School of Economics and Political Science suggests) can actually be VERY useful.

The trick to combining backcasting with storyboarding is putting the timeline at the top or bottom of the storyline. That is, if you’re going to do project backcasting, you can move around the project goals, activities and so on around the timeline (using Post-It adhesive notes, for example), but the timeline stays static. That way you can effectively plan where activities must take place and by when (specific deadlines). Those of us who actively storytelling would probably also enjoy storyboarding for project and paper planning.

Also, for those people who ask me who else does this kind of project and writing planning well, I find Dr. Ellie Mackin’s research planning website quite helpful. Ellie has a number of excellent templates for project planning, planning writing, etc. You may want to peruse it here. And hopefully my approach to backcasting a project may be of use to you! In my previous blog post on my yearly plan I also linked to several templates to reverse-plan a paper. You may want to check those.

Hopefully my process makes sense for everyone! It does for me.

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Continuing the Discussion