I have been writing a lot for a very long time, and I *still* find myself dreading the process of opening and facing a new document template.

The Dreaded Blank Page.

For many of us, facing The Dreaded Blank Page is an exercise in self-loathing, frustration and hand-wringing. Even though I write a lot, and I specifically focus much of this blog to the scholarly writing enterprise, I still find myself, on occasion, stumped and dumbfounded by The Dreaded Blank Page.

The way out, in my view (and this is what I preach to my students and research assistants and to anyone who will listen to me) is to gradually develop a writing practice and to make of each Dreaded Blank Page not a summit to CONQUER, but an issue that we have to to DEAL WITH.

He explained that he had read plenty of scholarly papers, and so on, but STARTING was the challenge. I have written about how to write a first rough draft of a paper in 8 steps https://t.co/QtktllEpGs and how to go from idea to a finished paper https://t.co/nMoL6ynrvp Later on…

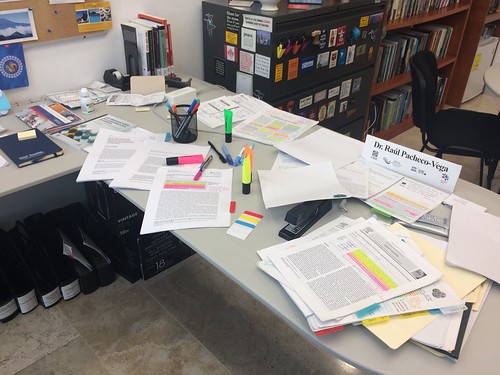

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

As a child, I used to read Charles Schultz’ “Charlie Brown”. I never realized I would actually be a writer when I grew up, but I strongly identified with Snoopy, and his approach to The Dreaded Blank Page:

“It was a dark and stormy night..”

That was his prompt, and it worked. pic.twitter.com/oAiSUae9fC

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

I have read many, many books on writing, but three that stand out specifically to help developing writing practices are:

a) @WendyLBelcher #12WeeksArticle https://t.co/IpJQewH8tw (2nd edition out just now)

b) @biblioracle ‘s “The Writer’s Practice” https://t.co/BwaFzY60O8

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

There are books that teach you how to practice and develop your writing skills, and books that teach you how to organize yourself to make the space for writing. The two best ones I have found for the latter are Jensen’s Write No Matter What and Zerubavel’s The Clockwork Muse.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

Anyhow, my students ask me “Professor, how do you deal with The Dreaded Blank Page?”

My answer: I use prompts (here are 5 suggestions) https://t.co/psTEwumZaE

I use devices (questions, topic sentences) or actions (data analysis, reporting, explaining) to prompt me to write.

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

(Here’s where @AliaGvR will jump and scream and say: THIS IS WHAT SCRIVENER IS MADE FOR!)

To deal with The Dreaded Blank Page, I always recommend that my students open a new Word document (several use LaTeX, but I’m a Micro$oft Office adopter what can I say). BUT people say…

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

1) break down the work in manageable pieces https://t.co/DhllyI1Ptp

2) focus on ONE piece of writing at a timehttps://t.co/4fcGi7XSHG

3) Consider spending time on that one piece of writing your Quick Win of the day https://t.co/tszIMHgogM or …

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

– from Brain Pickings https://t.co/Xs0UiFPuCI

– a cursory Google search https://t.co/DBPpOD8UYh

– a Twitter search https://t.co/jXhDwFSEuV

TL;DR: we all dread a blank page, but we can practice our way out of it. Writing is hard, but it’s a skill that can be developed. </fin>

— Dr Raul Pacheco-Vega (@raulpacheco) August 15, 2019

To recap, my suggestions to deal with The Dreaded Blank Page:

- Break down the project in smaller pieces.

- Deal with each piece of writing/research on its own.

- Use the completion of each small piece of writing as a Quick Win, or just focus on it for 30 minutes at a time.

Recent Comments